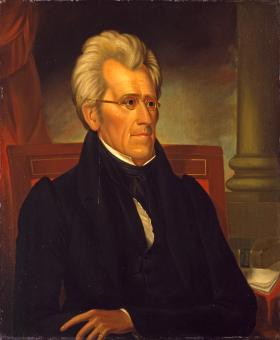

1. Show the three portraits Andrew Jackson, William Pitt, and Portrait of a Boy to the entire class. Define and discuss the use of symbolism (for example, the law book behind Jackson) in each of the works of art: What does the word “symbolism” mean? How are symbolism and the concept of meaning connected? How do artists use symbols to convey meaning in their work? Identify some symbols in the portraits. What do you think these symbols might mean? Talk briefly about the artists, particularly Ralph E. W. Earl and his responsibilities as Jackson’s “court painter.”

2. Provide an introduction to the life and contributions of Andrew Jackson, a native Carolinian who became president of the United States. Explain his involvement in the creation and passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and how it affected the Native Americans in North Carolina, particularly the Cherokees. Trace the path of the Indians out of the state along the Trail of Tears by displaying a map on the overhead. Discuss the conditions faced by those American Indians who stayed behind and disobeyed the law.

3. Assign students an important historical figure to research from the Trail of Tears era. Provide time for them to visit the school library or use the computer lab to search for resources. Instruct the students to complete a graphic organizer with important information about their assigned individual.

4. Once the research has been completed, reconvene the entire class and share the three historical portraits again. Reiterate how the artists used special symbolism in the pictures to illustrate key features of each of the individuals (such as Jackson wearing black mourning clothes to represent his grief over the loss of his wife).

5. Before distributing art materials, ask the students to brainstorm how they would like to illustrate their famous historical figure. Encourage them to sketch out a plan on a piece of notebook paper. Make sure that they include in their sketches several symbolic references to specific characteristics of their subject. For example, they may want to dress their person in certain clothes, add a background that suits the person’s native environment, or place specific objects around the person. The symbols should be used to convey a meaning about the person.

6. Allow the students an opportunity to paint, draw, or create digital portraits of their assigned historical subjects using their sketches as planning documents.

7. While the paintings are drying, introduce the concept of a cinquain poem. Demonstrate how to write this type of poem by creating one about Andrew Jackson as a group. A sample poem appears below.

Andrew Jackson person’s name

Strong, Powerful two adjectives describing the person

Leading, Vetoing, Fighting three action words

Born in the Carolinas four-word phrase

President nickname or noun

For additional examples, please see the Web sites listed in Lesson Resources.

8. Ask the students to create their own cinquains about the famous person that they researched. Mount the poems at the bottom of the historical portraits, and display them on a bulletin board for everyone to enjoy.

- Class discussion will be used to assess the students’ understanding of the ways artists use symbolism to communicate ideas and meaning, knowledge about the life of Andrew Jackson, and comprehension of the events surrounding the Trail of Tears.

- The teacher may review each student’s research or graphic organizer to determine whether the student was able to identify three key questions to research and find appropriate resources to answer the key questions in complete sentences.

- The teacher may use the paintings and accompanying cinquain poems to evaluate the students’ research, reflection on a historical person from this time period, and use of symbolism to convey meaning.

symbolism

Indian Removal Act

Trail of Tears

cinquain poem

Figures in North Carolina History

Ralph E.W. Earl was frequently called the "court painter" to Andrew Jackson, a somewhat ironic tag considering that Jackson, a Carolinian by birth, considered himself the champion of the common man. In this portrait, painted during Jackson's first term as president, Earl depicts the seventh chief executive from the waist up with one arm bent across his chest. Jackson's black mourning clothes (his wife died in 1828) add a measure of solemnity to his calm, self-assured appearance as he gazes into the distance. Earl's style produces crisp lines that distinguish the figure of Jackson and make him stand out from the muted background. A law book and sheaf of papers at Jackson's left elbow indicate the president's dedication to upholding and shaping the laws of his country.

Who was Andrew Jackson?

Andrew Jackson became a figure of national importance when an assortment of troops under his command defeated British forces at the Battle of New Orleans. Despite the fact that this battle took place weeks after American and British representatives signed the Treaty of Ghent to end the War of 1812, Jackson was celebrated for his unlikely victory and became the second-best-known military figure in the country, after George Washington.

The child of Scotch-Irish immigrants, Jackson was born in the Waxhaw community near the border of North Carolina and South Carolina in 1767. His father passed away in a logging accident a few weeks before his birth, and his mother and brothers all died from illness or injuries sustained in the Revolutionary War effort. Jackson served as a courier with the Continental Army during the war. An orphan at age 14, Jackson found employment teaching school but soon abandoned teaching to study law. He studied in Salisbury and was granted a license to practice law in 1787. He accepted a job as public prosecutor in the western territory of North Carolina, now Tennessee. Jackson was instrumental in the development of the territory into the state of Tennessee and served as that state's first congressman for a short time in 1796. Jackson maintained his ties to the military dating from the Revolutionary War. He become major general of the Tennessee militia in 1802 and a major general in the U.S. Army in 1812.

How did Earl become Jackson's "court painter"?

The son of portraitist Ralph Earl, Ralph E.W. Earl probably received his initial instruction from his father. While studying abroad, the younger Earl gained exposure to the European tradition of history painting: the depiction of events recorded in history, literature or the Bible. Earl returned to the United States in 1815 to begin an ambitious project about the Battle of New Orleans. Needing Jackson's portrait for his history painting, Earl met the general and cultivated a friendship with him during a visit to Jackson's Tennessee home in 1817. Earl became a part of the family when he married the niece of Jackson's wife in 1819.

Nine years later, Jackson's election as president was aided by populist changes in voting laws that allowed more men the right to vote. Earl went to live with Jackson at the White House in 1830. There he painted portraits of Jackson, many with a format similar to the example shown here. Earl charged $50 for a painting, and $20 more for a frame. The portraits reflect the image of a man known for strengthening the power of the presidency and the Union, the former through the use of the veto and the latter aimed at preventing states' defiance of federal law and possible secession. During his term of office, Jackson advocated a policy called the Indian Removal Act which required Native Americans to abandon their lands in eastern states and move to territories in the West.

William Pitt the Elder (1708-1778) is regarded as the greatest British statesman of the eighteenth century. Although he directed British government for only five years (1756-61), his energy, vision, and practical ability in conducting the Seven Years War led to the British victory over the French in North America and India, and secured the transformation of England into an imperial power. In 1766, Pitt delivered an impassioned plea on behalf of the American colonists who had resisted the Stamp Act, and, during the American Revolution, he continued to argue for moderation and calm in dealing with the colonies, advocating any settlement short of total independence. Pitt County in North Carolina is named after him.

Many early American artists traveled from community to community looking for subjects to paint. Jacob Marling decided to settle at the center of North Carolina political activity when he moved to Raleigh from Warrenton, where he had been a scenery painter in a theater. He painted and worked as an art instructor and decorator. He even worked as a museum director when the North Carolina Museum opened in 1813. The museum functioned as a reading room and featured collections of historical artifacts and curiosities.

Portrait of a Boy dates from this time. The subject, whose identity is not known, is depicted in a crisp linear style and sits in a mildly awkward pose against a backdrop of a scarlet curtain. He holds a book in his right hand to suggest his literacy.